History

A Rich Cultural Heritage

Indigenous influences. When the Acadian exiles arrived in Louisiana during the second half of the 18th century, they made settlements in various corners of the southern part of the colony, living alongside the existing population of Creoles, a broad category of Louisianians that included people of European, African, Afro-Caribbean and Indigenous ancestry. The mixture of influences in Cajun & Creole culture is evident in a rich oral tradition and repertoire of songs and dances. By the turn of the twentieth century, increasing homogenization of the United States threatened to doom the Louisiana French & Creole languages. Early versions of the Louisiana constitution made valiant attempts to legitimize the use of French, but America charged on with the nationalism movement. The approach of World War I induced a quest for national unity, which suppressed regional diversity.

In 1916, mandatory English language education was made available to the rest of Louisiana and was imposed in the South. French was trampled in a frontal assault on illiteracy. Several generations of Cajuns and Créoles were eventually convinced that speaking their native language was a sign of cultural illegitimacy. In the late 1940’s the tide seemed to turn. Soldiers in France during World War II discovered that the language and culture they had been told to forget made them invaluable as interpreters and made surviving generally easier. After the war, returning GI’s immersed themselves in their own culture. Dance halls throughout South Louisiana once again blared the familiar and comforting sounds of homemade music.

Musical Influences

In the 1950s and 1960s, South Louisiana like the rest of the nation and much of the world was affected by the emergence of rock and roll. The sons and daughters of Cajun and Creole musicians followed the musical lead of fellow Louisiana musicians Jerry Lee Lewis and Antoine “Fats” Domino to produce what was called swamp pop. Country music and swamp pop were tempting alternatives and Cajun music was again strained “to water the roots so that the tree would not die.” The needed impulse came from the national level.

Alan Lomax, a member of the Newport Folk Foundation, had become interested in Cajun and Créole music in the 1930s while collecting traditional music across the country for the Library of Congress. Harry Oster, a professor of English at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, recorded music, which stressed the evolution of Cajun music ranging from unaccompanied ballads to contemporary dance tunes.

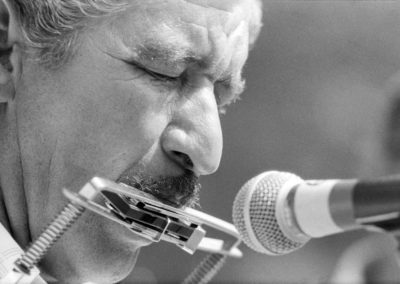

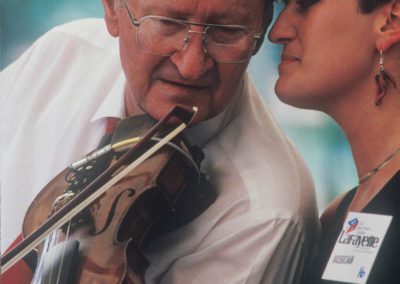

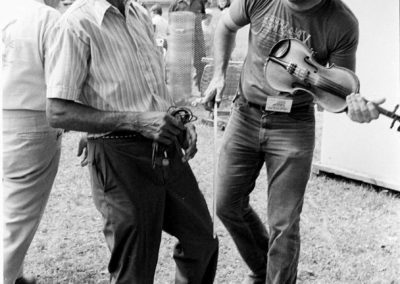

The work of Oster and Lomax caught the imagination of the Newport group and resulted in invitations to Cajun musicians Gladius Thibodeaux, Louis “Vinesse” LeJeune and Dewey Balfa to represent Louisiana at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival. They played alongside nationally known folk revivalists like Joan Baez, Peter, Paul, and Mary, and Bob Dylan. Despite poor reviews by the local press, Newport organizers were intent on showing the beauty and impact of root music.

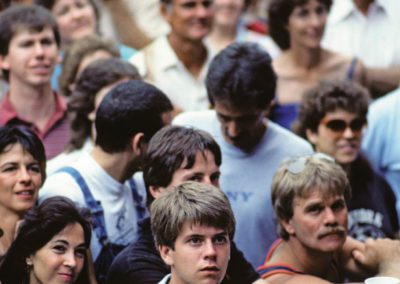

Their instinct proved well-founded as huge crowds gave the old-time music standing ovations. Balfa was so moved by the experience that he vowed to “bring home the echo of the standing ovation” they had received in Newport. With the help of the Newport Folk Festival Foundation, special concerts were presented so that people would have an opportunity to listen to their music without the distraction of smoke-filled dance halls.

The Cajun Cultural Revival

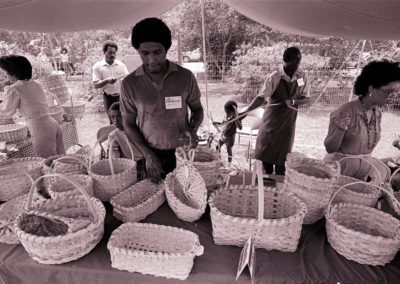

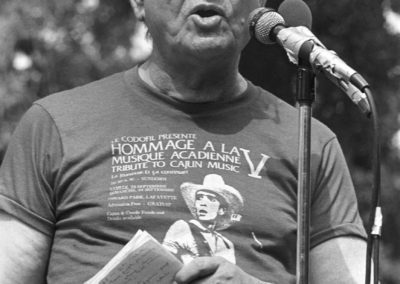

In 1968, the State of Louisiana officially recognized the Cajun cultural revival by creating the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL). Under the chairmanship of James Domengeaux, CODOFIL began its efforts on political, psychological and educational fronts to erase the stigma Louisianians had long attached to the French language and culture. In addition to creating French classes in elementary schools, CODOFIL organized the first Tribute to Cajun Music Festival in 1974. This three-hour concert was the catalyst needed to attract and educate the younger generation to the traditional values of the Cajun culture. Festivals Acadiens et Créoles is a cooperative of independent festivals that began in 1977. The oldest single component of this group was the Louisiana Native Crafts Festival (later to become the Louisiana Native and Contemporary Crafts Festival), first presented Saturday, Oct. 28, 1972, on the grounds of the Lafayette Natural History Museum near Girard Park.

On March 26, 1974, CODOFIL presented the first Tribute to Cajun Music concert in Lafayette’s Blackham Coliseum. In 1976, CODOFIL moved its Tribute to Cajun Music to Girard Park near the lake and to the fall. The Natural History Museum and CODOFIL agreed to hold their respective events on the same weekend. In 1977, the Lafayette Convention and Visitors Commission broadened the range, joining their own Bayou Food Festival, then held in the Lafayette Municipal Auditorium near the Natural History Museum. The combination of these three events focusing on the crafts, music and food of South Louisiana served as the basis for a co-op called Festivals Acadiens.

The Festivals Today

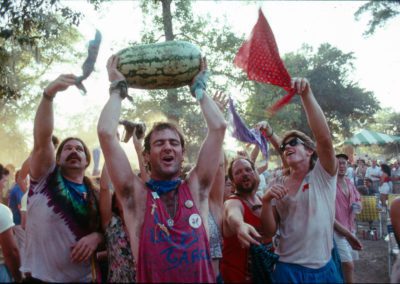

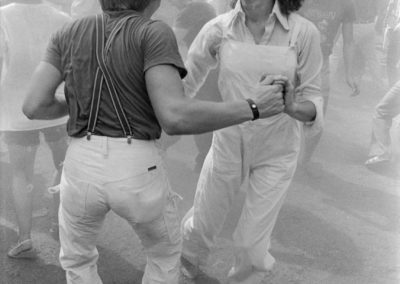

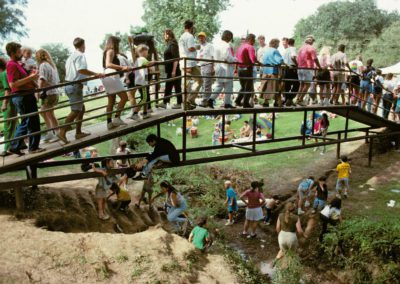

The Festivals’ events have continued to evolve, both on their own and together. The three grew first to become two-day and now three-day events. In 1980, CODOFIL’s annual Tribute to Cajun Music, which had already moved to the other side of Girard Park to accommodate growing crowds, was renamed the Festival de Musique Acadienne/Cajun Music Festival. Sponsorship of the music festival passed on to the Lafayette Jaycees who had already become involved in through the Bayou Food Festival and the Acadiana Fair & Trade Show. The Bayou Food Festival moved outdoors to make dancing and eating available in the same place. The Heritage Pavilion, the Atelier Stage, the Anniversary Stage, and the Jam Ça! Cajun & Créole Music Jam were added. The Louisiana Crafts Guild now produces the Louisiana Craft Fair in Girard Park.

In 2007, Festivals Acadiens developed a community board and became an independent non-profit corporation. In 2008, the co-op officially changed its name to Festivals Acadiens et Créoles in order to more accurately reflect the cultures that have always been the focus of all components. Since their foundations in the early 1970s, all three components have consistently championed creative cultural continuity. Organizers strive to present the current state of the culture through performances that can range from thoughtful preservation to daring innovation, from the oldest ballads to the latest in experimental Cajun music and zydeco, from traditional gumbos to crawfish eggrolls, from historical wooden boats to innovative multi-media folk art. And the Cajun and Creole musicians, cooks and craftsmen and women who participate in this annual event continue to invest themselves in what most rightly consider their own festivals, a self-celebration of Cajun and Creole culture.

A Rich Cultural Heritage

Acadians, or Cajuns as they are now called, were exiled from Nova Scotia in 1755. They took with them few possessions but did carry away a rich cultural heritage, which included a blend of French, Celtic, Scots-Irish and Native American influences. This mixture is evident in a rich oral tradition and repertoire of songs and dances. By the turn of the twentieth century, increasing homogenization of the United States threatened to doom the French language to obscurity. Early versions of the Louisiana constitution made valiant attempts to legitimize the use of French, but America charged on with the nationalism movement. The approach of World War I induced a quest for national unity, which suppressed regional diversity.

In 1916, mandatory English language education was made available to the rest of Louisiana and was imposed in the South. French was trampled in a frontal assault on illiteracy. Several generations of Cajuns and Créoles were eventually convinced that speaking french was a sign of cultural illegitimacy. In the late 1940’s the tide seemed to turn. Soldiers in France during World War II discovered that the language and culture they had been told to forget made them invaluable as interpreters and made surviving generally easier. After the war, returning GI’s immersed themselves in their own culture. Dance halls throughout South Louisiana once again blared the familiar and comforting sounds of homemade music.

Musical Influences

In the 1950s and 1960s, South Louisiana like the rest of the nation and much of the world was affected by the emergence of rock and roll. The sons and daughters of Cajun musicians followed the musical lead of fellow Louisiana musicians Jerry Lee Lewis and Anton “Fats” Domino to produce what was called swamp pop. Country music and swamp pop were tempting alternatives and Cajun music was again strained “to water the roots so that the tree would not die.” The needed impulse came from the national level.

Alan Lomax, a member of the Newport Folk Foundation, had become interested in Cajun and Créole music in the 1930s while collecting traditional music across the country for the Library of Congress. Harry Oster, a professor of English at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, recorded music, which stressed the evolution of Cajun music ranging from unaccompanied ballads to contemporary dance tunes.

The work of Oster and Lomax caught the imagination of the Newport group and resulted in invitations to Cajun musicians Gladius Thibodeaux, Louis “Vinesse” LeJeune and Dewey Balfa to represent Louisiana at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival. They played alongside nationally known folk revivalist like Joan Baez, Peter, Paul and Mary, and Bob Dylan. Despite poor reviews by the press, Newport organizers were intent on showing the beauty and impact of root music.

Their instinct proved well-founded as huge crowds gave the old-time music standing ovations. Balfa was so moved by the experience that he vowed to “bring home the echo of the standing ovation” they had received in Newport. With the help of the Newport Folk Festival Foundation, special concerts were presented so that people would have an opportunity to listen to their music without the distraction of smoke-filled dance halls.

The Cajun Cultural Revival

In 1968, the State of Louisiana officially recognized the Cajun cultural revival by creating the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL). Under the chairmanship of James Domengeaux, CODOFIL began its efforts on political, psychological and educational fronts to erase the stigma Louisianans had long attached to the French language and culture. In addition to creating French classes in elementary schools, CODOFIL organized the first Tribute to Cajun Music Festival in 1974. This three-hour concert was the catalyst needed to attract and educate the younger generation to the traditional values of the Cajun culture. Festivals Acadiens is a cooperative of independent festivals that began in 1977. The oldest single component of this group was the Louisiana Native Crafts Festival (later to become the Louisiana Native and Contemporary Crafts Festival), first presented Saturday, Oct. 28, 1972, on the grounds of the Lafayette Natural History Museum near Girard Park.

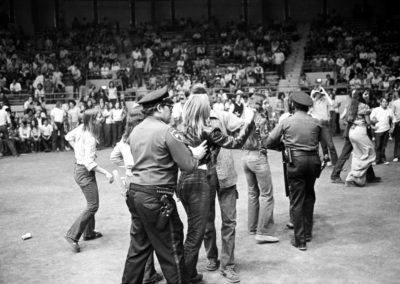

On March 26, 1974, CODOFIL presented the first Tribute to Cajun Music concert in Lafayette’s Blackham Coliseum. In 1976, CODOFIL moved its Tribute to Cajun Music to Girard Park near the lake and to the fall. The Natural History Museum and CODOFIL agreed to hold their respective events on the same weekend. In 1977, the Lafayette Convention and Visitors Commission broadened the range, joining their own Bayou food Festival, then held in the Lafayette Municipal Auditorium near the Natural History Museum. The combination of these three events focusing on the crafts, music and food of South Louisiana served as the basis for a co-op called Festivals Acadiens.

The Festivals Today

The Festivals’ events have continued to evolve, both on their own and together. The three grew first to become two-day and now three-day events. In 1980, CODOFIL’s annual Tribute to Cajun Music, which had already moved to the other side of Girard Park to accommodate growing crowds, was renamed the Festival de Musique Acadienne/Cajun Music Festival. Sponsorship of the music festival passed on to the Lafayette Jaycees who had already become involved in Festivals Acadiens through the Bayou Food Festival and the Acadiana Fair & Trade Show. The Bayou Food Festival moved outdoors to make dancing and eating available in the same place. The Heritage Pavilion, the Atelier Stage, the Anniversary Stage, and the Jam Ça! Cajun & Créole Music Jam were added. The Louisiana Crafts Guild now produces the Louisiana Craft Fair in Girard Park.

In 2007, Festivals Acadiens developed a community board and became an independent non-profit corporation. In 2008, the co-op officially changed its name to Festivals Acadiens et Créoles in order to more accurately reflect the cultures that have always been the focus of all components. Since their foundations in the early 1970s, all three components have consistently championed creative cultural continuity. Organizers strive to present the current state of the culture through performances that can range from thoughtful preservation to daring innovation, from the oldest ballads to the latest in experimental Cajun music and zydeco, from traditional gumbos to crawfish eggrolls, from historical wooden boats to innovative multi-media folk art. And the Cajun and Creole musicians, cooks and craftsmen and women who participate in this annual event continue to invest themselves in what most rightly consider their own festivals, a self-celebration of Cajun and Creole culture.