50 Years

Since then, the components of Festivals Acadiens continued to evolve, both on their own and together. The three initial components grew to become two-day events. In 1980, CODOFIL’s annual Tribute to Cajun Music, which had already moved to the other side of Girard Park to accommodate growing crowds, was renamed the Festival de Musique Acadienne/Cajun Music Festival. In 1980 sponsorship of the music festival passed on to the Lafayette Jaycees who had already become involved in Festivals Acadiens through the Bayou Food Festival and the tangentially related Acadiana Fair & Trade Show, which was later discontinued. The Bayou Food Festival moved outdoors to Girard Park to make dancing and eating available in the same place. The Louisiana Crafts Guild developed a contemporary crafts component for the festival; initially held in Lafayette’s Heymann Performing Arts Center, it eventually moved to Girard Park in 2003 and subsumed the native crafts focus as well. The City of Lafayette’s Downtown Alive celebration joined the party along the way with a Friday night opening concert. The co-operative venture was run through the LCVC for the next few decades.

Some of the festivals organizers and programmers, especially Keith Cravey, Vance Lanier and I, actively sought out guidance and experience in festival production by volunteering and getting hired at other major festivals, such as the Smithsonian’s Festival of American Folklife, the National Folk Festival, the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, the Louisiana Folklife Festival, the St. Louis Frontier Folklife Festival, San Antonio’s International Accordion Festival, Québec’s Festival d’Eté, its Festival International des Arts Traditionnels and its Festival de la Nouvelle France, New Brunswick’s Frolic des Acadiens, and Nova Scotia’s Festival Acadien.

By the early 2000s, the Lafayette Jaycees were dwindling in numbers and eventually relinquished its sponsorship after 2006. In 2007, a few of the festival veterans took control of the event. We developed a community board and became an independent non-profit corporation. I, who had been responsible for programming since the first concert in 1974, became president. The other founding members of the board included two veterans from the Jaycees years and two long-time festival volunteers. Linzee Lagrange who was responsible for processing the money the festival generated became the board’s treasurer. André Mitchell who organized the logistics, became a vice-president. Patrick Mould, who had helped to expand programming became a vice-president. And Helena Putnam, who had been active in programming as well as stage and backstage organization, became our secretary. One of the first things the board did was work to stabilize the event’s finances. We immediately applied for and received 501(c)3 status. Until then, the festival had been essentially funded by the sale of beverages, especially beer, which was financially and morally unsound. A history of limited funding base had given us no room to expand or improve the event. The fact that we had survived and remained popular all those years on such a flimsy basis was nothing short of miraculous. In addition, a partial rain-out in the first year under the new board seriously jeopardized the future of the festival. Patrick Mould took on the responsibility of engaging in fund-raising through the acquisition of corporate and business sponsorships. No one had explored this angle until then. The challenge was to get to the point where the entire weekend was financially secure before the first note was played. Mould reached that goal by the third year. Since then, the festival has accumulated enough money to insure survival through several rainouts. Two of the first issues we addressed with our new-found financial stability were raising fees to performers and improving the look and infrastructure of the event (nicer tents, staging and sound). We also began to provide support for cultural and linguistic development through a grant program that has enabled young musicians, aspiring chefs and craftspersons to improve their French and their skills. We continued the initiative begun under the previous structure to support research on Cajun and Creole culture and language through the university’s Center for Acadian and Creole Folklore.

These funds have been used to purchase recording equipment, blank tapes and cameras, to underwrite student fieldwork projects, and to obtain research materials such as books, documentary films, sound recordings, and photographic images. Among the important projects funded by these donations are the Center for Acadian and Creole Folklore’s copies of historical Louisiana French field collections, including those of John and Alan Lomax, Elizabeth Brandon, Harry Oster, and Ralph Rinzler, among others.

We initiated a sponsorship program, providing support for young musicians, artisans and chefs to learn about the language, culture, history and art of our heritage. We also undertook to improve our annual “home” in Lafayette’s Girard Park, which was suffering from decades of neglect and underfunding by the city, planting grass to prevent erosion and planting fruit trees to replace trees that had died or been damaged by storms. Our financial stability also enabled us to produce and support other events during the year, including a cooperative arrangement with Lafayette’s other major music and culture event, Festival International, as well as products and events related to our mission, such as CDs, books, art and photographic exhibitions, and symposia. The basic principle is to invest in the future of the cultures we present.

In terms of programming, we were initially inspired by musician and community scholar Dewey Balfa who had worked with Ralph Rinzler (who in turn was inspired by Alan Lomax) at the Newport Folk Festival beginning in 1964 and then at the Smithsonian’s Festival of American Folklife through the 1970s and ‘80s. Balfa worked tirelessly along with others, many of whom had also been affected by Rinzler’s fieldwork trips to the region, including Revon Reed and Paul Tate, to change the hearts and minds of his own community. When he met with CODOFIL chairman Domengeaux in 1973, he took the opportunity to discuss his ideas concerning the potential importance of the music in Domengeaux’s effort to revitalize French in the state. A few months later, when Domengeaux was looking for a cultural event for the French-speaking journalists, some of us who had been influenced by Balfa proposed a concert that would pay serious tribute to Cajun and Creole music.

Domengeaux was also looking for a mass rally that would serve as a public demonstration of grassroots support for the CODOFIL movement, which had been criticized by many as elitist since its inception in 1968. A program devoted to Cajun and Creole music would serve as a show of support for the state’s indigenous French culture. Domengeaux appointed a committee, headed by Paul Tate, to study the issue and propose plans for the event. Transcripts from the committee’s initial meetings show that the concert format was suggested independently by Balfa and by Louisiana French teacher Richard Guidry, who both reasoned that if we prevented the audience from dancing, they would listen to the music in a different way. The concert format would also provide an opportunity to present historical and cultural commentary. Over several months, the committee identified potential performers and discussed strategies to organize the message. As a French major at the University of Southwestern Louisiana (now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, I had already begun doing fieldwork in the area, influenced in part by Balfa. As a student aide at CODOFIL, I participated in the discussions that led to Domengeaux’s decision to produce the concert. I worked with the committee in its meetings and with Rinzler by telephone to develop a concept for the event, but I knew little about actual production. Committee member and La Louisianne Records owner Carol Rachou dispatched his student worker Keith Cravey to help with the logistics. Together, we served as CODOFIL’s production team. We eventually decided to hold the concert in the Blackham Coliseum with a seating capacity of 8,400, after also considering the university’s student union ballroom, its theater, and Lafayette’s Municipal Auditorium. The size of the venue placed pressure on our plans. Domengeaux rightly assessed that the project could blow up in our faces if it were not a significant success, especially before the 150 French-speaking journalists who would be in attendance. Even a few thousand people would look lost in the place and give the impression that the French cause in Louisiana was hopeless. On the other hand, with anything approaching a full house, the message of hope could be dramatic. Not untypical of his political past, Domengeaux had decided to go for broke, betting our collective fortunes on that evening.

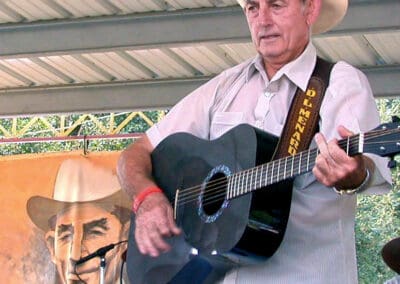

The concert, called “A Tribute to Cajun Music,” reflected the plan developed by the committee and the producers, under the guidance of our various advisors. Rinzler, who had become Director of Folklife Programs at the Smithsonian Institution and Director of its annual Festival of American Folklife, lent his support and the prestige of his office by introducing the program. Additionally, University of Southwestern Louisiana Honor Professor of French Hosea Philips served as master of ceremonies. Tate and Domengeaux gave prefatory remarks about the cultural and linguistic importance of the music. The program presented the history and development of Cajun and Creole music from unaccompanied ballads through early instrumental styles to contemporary developments. A group of dancers demonstrated a 19th century quadrille. All performers, from ballad singer Marcus Landry, whom Rinzler added to the program after hearing him sing that afternoon, to Zydeco King Clifton Chenier, invested themselves in the project, donating their time and talent.

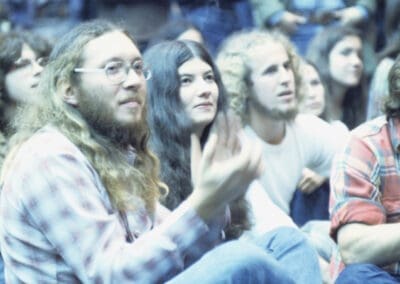

The idea to present the music in a concert format seemed to work on several levels. First, prevented from dancing, members of the audience listened to the music in a different way. This was clear from their reaction after the first song; they applauded. This was not something one heard in the dancehalls where, after a song, dancers simply escorted their partners back to their tables and arranged for the next dance while visiting with their friends and neighbors. The formality of the presentations and the ongoing commentary also added another layer to the evening. So did the four-foot-high stage and concert-style sound system. For their part, the musicians had to negotiate new contextual territory as well. Some of them, such as the Balfa Brothers, Nathan Abshire, Dennis McGee, Marc Savoy, and the Ardoin Family, had considerable experience on the national folk festival circuit. Clifton Chenier had experience of a different kind, having toured with national rock and blues performers. But even they had never seen this kind of crowd in this kind of setting on their home turf.

Since their foundations in the early 1970s, all three components of what has become Festivals Acadiens et Créoles have consistently championed creative cultural continuity. Organizers strive to present the current state of the culture through performances that can range from thoughtful preservation to daring innovation, from the oldest ballads to the latest in experimental Cajun music and zydeco, from traditional gumbos to crawfish eggrolls, from historical wooden boats to innovative multi-media folk art. And the Cajun and Creole musicians, cooks and craftsmen and women who participate in this annual event continue to invest themselves in what most rightly consider their own festivals, a self-celebration of Cajun and Creole culture.

The chronology of schedules and performers traces the constantly evolving philosophy of cultural activism among festival producers. It shows who played when, in what order. The rationale behind this long-term cultural experiment can be teased out of the scheduling, the description of the bands, and the festival dedications over the years. Almost all of these were originally articulated and composed by me for the various festival programs and some of the accompanying articles that have appeared in the local media, especially Lafayette’s Daily Advertiser and the Times of Acadiana. Eventually, the festival press coverage generated some interesting commentaries concerning tangential issues, such as the growing popularity of the musicians and the inherent difficulties of resolving the need to play on the road and the importance of staying rooted. Underpinning all of this is the constant tension between preservation and innovation, between the past and the future. A fundamental principle of the festival is that tradition is not a fixed product but an ongoing process, that culture is a living organism. To try to prevent this is not only unwise but impossible. As I wrote many years ago in Cajun and Creole Music Makers (Austin: U of Texas Press, 1984; revised, Jackson: U Press of Mississippi, 1999):

Rarely conforming to notions of what it should be, Cajun music continues to be what an unruly lot of Cajun musicians insist on playing every weekend, at house dances and in dance halls, on front porches and on main festival stages. Like Cajun culture, it is a clear reflection of the people who live it. It is, to the dismay of the soi-disant elite, art in the hands of the people. (151)

A corollary of this fundamental principle is that creation and conservation are partners in a symbiotic relationship. There is a vital dynamic that is produced when the two forces work together. This festival has long championed creative cultural continuity. On its stages we try to present the current state of the culture through performances that can range from informed and innovative revivals of the past to informed and innovative explorations of the future. Music that seems to be the result of this organic process has interested festival programmers most. There are several measures for this consideration, including poetic French lyrics, tight arrangements, solid musicianship and group dynamics, and fairly unselfconscious presentation. The music can be obviously affected by outside influences, such as rock, country, the blues, jazz, even hip-hop, but it must organically integrate them. There is a difference between southern-rock-influenced Cajun music and southern rock played by a Cajun musician, between rhythm-and-blues influenced zydeco and rhythm and blues played by a zydeco musician. Festival programming also consciously manipulates some situations, bringing former bandmember back together for reunions, recycling faded traditions, such as ballad singing, jurés and twin fiddling, and juxtaposing groups to create tacit messages concerning such issues as the broad range of styles (Dewey Balfa and Zachary Richard) and the flow of cultural transmission (the Savoy Family and the Pineleaf Boys). We also sometimes ask performers such as Joel Sonnier and Wayne Toups to feature the French side of their repertoires so that their performances will enhance this musical celebration of Cajun and Creole culture. Somehow, it seems to work. Musicians continue to invest themselves in what most rightly consider their own festival.